If you know him at all, you no doubt have an opinion of Chip Wilson, the resigned billionaire founder of Lululemon.

Though he is no longer in an active role with the famed athleisure brand he founded in 1998, Wilson isn't sitting on the sidelines of retail, living out his days merely climbing the mountains of British Columbia in Canada. He is a prominent investor in many celebrated brands, like Arc’teryx, and still casts a long shadow over the worlds of vertical retail and direct to consumer business.

From his home in Vancouver, Wilson discusses the death of wholesale, his relationship with Lululemon and its CEO today, and the dangers of chasing short-term revenue. “It's so easy to go on discount and to sell the soul of the brand over a three- or four-year period and make the numbers look really good, which makes the CEO look like a hero to Wall Street,” he says. “But [the CEO] has really undermined the value of the brand.”

(This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.)

What have been your observations on the state of the industry these days? What kind of mark do you think 2020 is going to leave on retail as we move forward?

Wilson: Well, there's no doubt that the [COVID-19] crisis has moved the technology—what I call the “hockey stick”—10 years in advance overnight. That wouldn't be a surprise to anybody. Everyone's moving to ecommerce. Everyone's moving digital.

Right now, we're in a time when probably half of the retailers are going to go bankrupt unless landlords really move quickly and cut their rents in half. I see that maybe in two years from now, rents will be half of what they are now, and then I think it's going to be a great opportunity for all these small brands and retailers to move back in—do retailing, but then have ecommerce, something like Shopify, right alongside them.

We won't see stores as we did before when they're mono[channel]. Almost half the store could be set up to only sell ecommerce, and the other half of the store could only be set up to sell right then and there for people.

Had 2020 happened during your tenure leading Lululemon, do you have a sense of what the most important considerations you would have had to make to weather this storm?

Wilson: I always go back to 2008. I don't think it's any different. Never let a good crisis go to waste. I think [the 2008 recession was] the best thing that ever happened to Lululemon at the time, and I think this is going to be the best thing that's going to happen to a lot of businesses.

So for instance, at that time, I'd been holding off on doing ecommerce at Lululemon for a couple years because I couldn't even supply our own stores—the brand was just so hot. But we brought in ecommerce, and it really helped us move our inventory. We launched into ecommerce, we got to learn about it, and because we started so soon on it and we had such great demand, I think our ability to make a great ecommerce platform was phenomenal.

The obvious thing then is that everyone makes their processes. Brands like Shopify or Lululemon are probably growing so fast there's a bunch of things you wish you could get at, but there's just so much money to be made, you can't get at the processes. By having a year to slow down and get your feet underneath you, the companies that have any kind of a solid foundation and aren't losing money hand over fist are going to come out at the end of this Darwinism and do phenomenally.

If they're using this time to really get their processes down, get their people culture down, and their people development down, when the time comes to grow, they can grow exponentially.

I heard you suggest recently that partial store re-openings are in fact more costly and perhaps more damaging for companies than simply staying closed altogether. Can you help us understand that idea a little further?

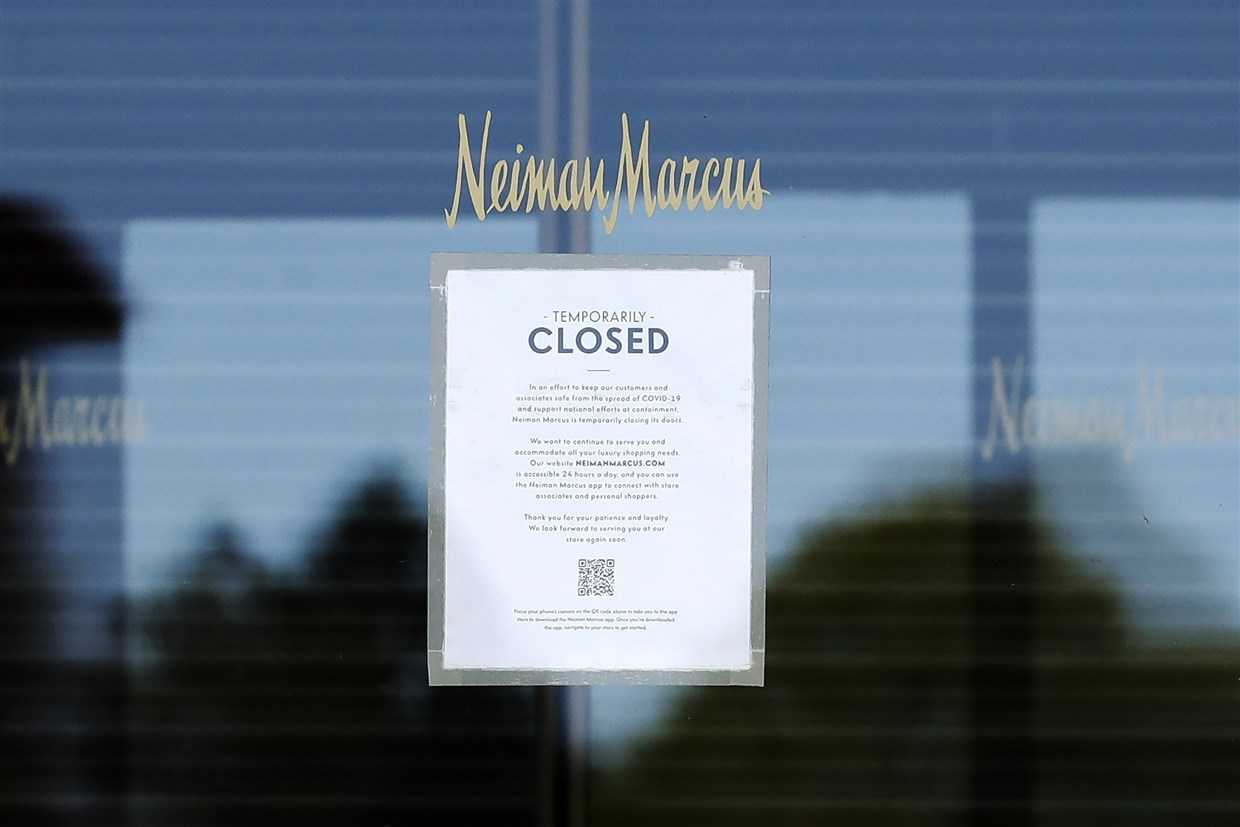

Wilson: Let's say a restaurant or a retail store doing 100% capacity is making a profit. But the underlying costs of running a business like that—with the rent, the lights, the employment, wages, et cetera—probably means the business breaks even if it did 80% of that revenue. Already, before COVID, ecommerce was already eating into that 20%. It had actually eaten it up. So I'd say most retailers were at best breaking even. You can see a lot of big U.S. retailers have gone bankrupt and gone out of business or are in Chapter 11.

So we're already at break even, and then COVID just took it over the edge. So I see very few businesses being able to survive in this realm. I'd say easily half the retailers in North America and in Europe won't be able to make it.

Lululemon officially launches in 1998, and before committing significant resources to a store in a new city, maybe a year in advance you arrive with a popup shop, or some kind of temporary activation to get some buzz going. And then if that works, you decide it's right to invest money in that new geography to open up retail more officially.

Anyone that's ever read a business textbook knows word of mouth marketing is the best kind of marketing, but few know how to do it really well. In its early days, what were the ways that Lululemon managed to achieve results with word of mouth marketing?

Wilson: It came out of, “Invention is the mother of necessity.” We had no money. As far as the stores go, really, we fell into that popup store by mistake. And nobody had ever done it before because nobody had really owned their own retail store. No one brand that was designing their own clothing and manufacturing their own clothing and had their own retail store. There were always a couple of middle men in there.

We found out that by opening up our own store, we were letting the quality of the product and the quality of the development of our people be what people went into the store to buy or to experience. And we put out a better quality product at a better price than any of our competitors, so nobody could compete with it. So then people come in, try the product on. It was radical for a lot of different reasons, but then people go and talk about it.

Having stores that were popup stores in the middle of a neighborhood, we would work with the yoga studio instructors. They would become our community. Those were our heroes. And it didn't cost us very much. Really, they were the people that did the talking for Lululemon. We just did it organically. We never pushed. We always pulled.

Another thing that Lululemon does in the late '90s is, if you don't precisely invent vertical retail for a brand operating in your space, you're darn close to doing so.

At that time, if you were a brand, you most often made your goods and sold them at another company’s store. But you observe that, by selling your own goods, you're the manufacturer, the wholesaler, and the retailer, and you could triple your profits by being all three. What was the climate then as it pertained to vertical retail, and what were the challenges to pulling it off for Lululemon?

Wilson: There were very few retailers [doing it]—maybe the Gap, but they were selling Levis’ mostly. The real challenge of setting up a vertical operation is economy of scale production. In other words, if you're doing wholesale, you can make a line of clothing, then go sell it to a bunch of people, and they put in orders, and then you have enough numbers in order to go to a factory and get it made.

The toughest part with something like Lululemon is that we needed to get to probably 10 or 12 stores in order to have enough volume going through before we could make any money. So I basically had to keep our prices low, as though I was doing economy of scale production, and lose money in order to make sure that I had enough people buying the product to make sure I could put enough through the manufacturers to make my margin.

It's kind of a suffering point of view, but it usually takes a lot of money, and we didn't have a lot of money. But I think we just had a phenomenal product, and I'd been doing production and designing in retail stores for 20 years, so I knew the puzzle that I had to put together to make that occur.

We spoke with Tim Brown (pictured above), who co-founded Allbirds, and we asked Tim if he thought he could reach as many people as the brand had ambitions to by sticking to selling direct to consumer. He cited Lululemon as the template for how Allbirds could do just that.

Are these really new, cool, successful brands right to largely steer clear of wholesaling, and follow in the model Lululemon lay before it to insist on always reaching customers directly?

Wilson: Yeah. I think what we're seeing is the death of wholesale. If you had to look at the companies that are surviving now and the ones that are dying, anyone in wholesale is dying. Even to some extent, Nike, Under Armour, and Adidas just got killed in the Sports Authority bankruptcy of 2016. The only reason I think Nike did a sell-your-soul agreement with Amazon was to move that inventory. And once they moved that inventory, they said, "That's the end of our agreement with Amazon." They went on their own.

Lululemon's always been there and probably has got the purest brand because it doesn't sell to anybody else. So there's absolutely no discounting, [there’s] total control of the brand, and it doesn’t go through wholesalers who interpret it as they want to, which I think is the death of brands. That's got to go by the wayside. I think ecommerce is just allowing everybody to go direct to consumer.

Lululemon has a few outlet stores, and its products do go on sale, but the company isn't precisely known for slashing its prices throughout the year. What was the philosophy behind your approach to discounting at Lululemon?

Wilson: My philosophy is every dollar you discount takes $10 off the market capitalization of the company. Mostly what happens is merchandisers and buyers are set up on a one-year bonus program [based on] how their margins or sales went that year, but that has no correlation to the brand value. And most CEOs I'd say that I see coming into companies don't understand that correlation at all.

It's so easy to go on discount and to sell the soul of the brand over a three- or four-year period and make the numbers look really good, which makes the CEO look like a hero to Wall Street, but [the CEO] has really undermined the value of the brand and the future discounting ability. So in other words, if you keep discounting, then at some point people don't believe in your discount and they don't buy what it is you want them to buy.

It's been my experience that once every three years, you have either your designers mess up or your buyers mess up, and you have too much inventory, and you need to be able to discount. If you've been discounting all along, then you can't discount when you really need to. Or you have a 2008 crisis or a COVID crisis when suddenly you've got a lot of inventory, and you need to move that. If you've got a weak brand that's been set up by discounting, then your chances of getting into trouble are exponential.

There's a semi-famous proclamation you've made once that you're able to visit a retail store, and within 10 minutes you can confidently take stock of how healthy or unhealthy the company's finances are just by having a look around. Can you explain that, and what you look for as markers of success or failure when you enter a retail store?

Wilson: Maybe it's Malcolm Gladwell's 10,000 hours that he talks about. I’d had 10,000 hours of being in retail stores, manufacturing, developing people, and then to walk into a retail store—I can't even quantify it, but I think a lot of it is feeling.

I can tell if a light is out or lights aren't shining in the right place, or there's a dust bunny in the corner, or there are cardboard boxes sitting out when they shouldn't be, or how soon an employee in the business comes and talks to me and how they talk to me. There are a million nuances of things that occur in a retail store, and I think they just all flood in at one time.

You served as CEO of Lululemon until 2005, at which point you brought in outside investors to the company. Over the next 10 years, you accumulate a good chunk of your fortune, yet your tensions with the board at Lululemon play out quite publicly, and you might agree that it's fair to say you had some significant disagreements about the direction the company takes before you ultimately leave in 2015. How would you characterize your relationship with Lululemon today?

Wilson: I think my relationship with the CEO is fine. We go for walks and talks.

For a great brand like Lululemon, the real money comes from the product, the innovation, and the brand. But the problem with brand product innovation is it's not quantifiable. So if somebody comes with an idea that is not quantifiable, it [can] get shot down.

Here's the analogy I give: If the public analysts and the board kept telling Amazon, "Start showing a profit. Start showing a profit. Spend less," because they want to see some profit so they can sell the stock or whatever it is those guys do. If Jeff Bezos had slowed down spending, Amazon would only be worth half of what it is now. So let's say it'd be worth $600 billion. Well, people around the world would go, "That's a fantastic company. That's unbelievable. Whoa, what a great job the board did." But the reality of it is that if he would have stopped spending in order to become [just] the best ecommerce company in the world, it would have only been worth half of what it is now.

So when people say something like, “Lululemon, wow, it's an incredible company. Look at the value of it. Aren't you happy?" I go, "Well, no, because it's only worth half the value that it can be."

In preparing for this interview, I read a lot about you and your story, and I think you know that there are a lot of good things that exist about you in the public discourse, and I think you're also self-aware enough to know that certain narratives about you seem to persist in the general reflections of you as a man and a business person. Do you feel secure at present in your legacy—that you'll be remembered in the ways you hope to be?

Wilson: (Pauses) I don't know. I know that if you look at what has occurred out of Lululemon—the hundreds of millionaires, and the hundreds, if not thousands, of women especially that were trained and developed at Lululemon at a time when no other company would invest in women, who have gone on to set up their own businesses, been highly successful, had families, children, lived the dream—I think Lululemon started that whole thing out for women. I think that anyone who worked for me or who knows me will see that will be my legacy.

But I'm not sure that I can ever overcome the whole social media thing that occurred. There's no way a man or a woman who has a point of view in this world can't have enemies. And it's impossible for someone who foresees the future to say anything about the future without people that don't like change jumping on it and having their point of view.

I was probably one of the first people for that to happen to, and it's still happening today. I mean, we're in a very weird social media world where free speech is no longer allowed, another point of view isn't allowed.

Everyone has a point of view behind the screen of a computer. So I have to be happy with the legacy that I've left with the people that I've known and touched, and I'm thrilled for that.

Can I wrap up here, Chip, by having you peer in your crystal ball for us a little?

Wilson: Okay.

You are “widely considered to be the creator of the athleisure trend,” and I know you're widely considered to be that because I lifted that exact quote from the intro paragraph to your Wikipedia page.

Wilson: (Laughs)

If we agree that in the late '90s and early 2000s, athleisure was the thing the consumer market didn't yet know it wanted, do you have a sense of what incoming trends in retail like that we ought to be paying attention to now?

Wilson: I think everyone's going to be wearing technical clothing of some sort. Unless you're in the very heat of the middle of the equator where I think really light cotton is the technical apparel that works, the rest of the world is going to be demanding clothing that’s one piece that you can wear all day long—to a five-star restaurant, into a workout, for coffee, to work, the whole thing—without changing. It won't stink. It'll stretch. It'll take all your vitals. It'll send messages to your doctor. I think you won't even notice that it looks like athletic wear.

I think it could look like the cleanest of nice streetwear that we have right now. But it could even go back to suits and ties, which seems like a crazy idea to me, but even the tie would be stretch. It would feel like you had your athletic clothing on when you had your suit on.

Of all the things we saw affect retail and ecommerce over 2020, what things in your view are just a matter of time before they mostly return to the way they were, and what things in your view are changes to retail and ecommerce that are here to stay?

Wilson: I think that rents are going to drop in half, and you're going to see really vibrant streets where people can walk and socialize. But you'll walk into a store and it'll be totally set up to present the brand physically how the brand wants to be seen. That includes not just the apparel, but the ambiance of the store, the music, the smell, how the people are developed, and how they interact with the customer. I think that people will have total choice on anything—to buy ecommerce or buy there in person.

Because people are essentially social, I think people do want to get out. Obviously, the movement pre-COVID was that movement towards social workouts and classes. But instead of having a [separate] workout place, I think that's going to be the experiential part of the retail store, and you're also going to have connected organic food to it. Because it's so easy to buy off ecommerce now, a retail operation has to have more of the experiential.

So if people are going to their workout classes, staying and buying some food, and there's really great product to buy while they're there, they'll buy it.