When the place we call home is also the place where we work and create, it defines us as much as we define it. Makers and founders everywhere are at the heart of the communities where they do business. This series, And Nowhere Else, examines the relationship between the places they live and what they choose to create.

Peppered with historic districts and more than 1,600 temples, Kyoto is where the past meets the present. The art of crafting can be traced back to makers who serviced the royal family in this onetime capital.

But a new wave of creators are carrying on the tradition with a twist in this city—the historical heart and spiritual center of Japan. They’re morphing kimonos into guitar straps, altering the classic method of gift wrapping, and showcasing the bento box in a new light. And they’re evolving longlasting customs by finding new niches and expanding into new territories.

The gift of giving

Historically, visitors entered Kyoto by crossing the Sanjō Ōhashi, a bridge over the Kamo River. The path following the bridge is home to a historic, narrow street that locals and tourists love to roam. Along the path sits Musubi Furoshiki, a shop established in 1937 that’s dedicated to designing and crafting furoshiki, a traditional square wrapping cloth used for gifting.

Etsuko Yamada, Musubi Furoshiki’s owner, values the bond between furoshiki and kimonos—a throwback to the cloth’s original name—koromo zutsumi.” When nobles strolled the streets of Kyoto in historic times, their kimonos would change with the seasons, and so did the cloth that they used to wrap and carry them. This tradition is the genesis of Etsuko’s family business, but the third-generation owner is finding new ways to gift-wrap and promote an environmentally conscious way of living. “Japan has a problem with the use of plastic bags, paper bags, and creating tons of garbage,” says Etsuko. “But if people realize how useful furoshiki is, it can be used repeatedly, and it has multiple uses for many occasions.” In classes and videos, Etsuko showcases how furoshiki can be folded into purses, wrapped around wine bottles, and used for groceries. And her designs live beyond Japan’s borders, most notably in France.

Resurrecting kimonos from recycling bins

When Ayumi Nicholas first moved to Kyoto, she struggled to find unique and colourful straps for her guitar. Inspired by a trip to a temple’s market, she found vintage kimono and obi fabrics and realized that she could turn discarded silks into guitar straps. She soon launched Singing Crane to “make a new story” and give the kimonos “another life.”

The kimono was born and perfected in Kyoto, when imperial and noble families, and their kimono makers, lived here. But as life modernized, the kimono evolved from everyday wear to occasion fare, and many ended up in the recycling or vintage shops. For Ayumi, whose grandmother was a kimono maker, upcycling kimonos creates personal nostalgia. “My grandmother...taught me a lot about the old style of the kimino,” recalls Ayumi, who opts to sell online instead of in a physical shop. But she visits vintage shops each week to source fabrics. One store, Gypsy Bus, also assists her with production, incorporating the city’s colors of black, brown, and gray with bright tones of obis and kimonos before some pieces ship as far as Australia, the United States, and Europe. “When I send my guitar straps overseas, I feel really happy,” she says. “I’m wondering what kind of home they’re going to have.”

Close-knit community

Countless needles and weaving machines thread through Kyoto’s craft-making lineage, but locals bring that spirit to life. Through a chance meeting on Ravelry, an online community for knitters, Tokuko Ochiai and Meri Tanaka discovered they both grew up with similarly crafty childhoods and inspired each other to take on more complex knitting designs and master techniques. They decided to share their knowledge by launching an online magazine, Amirisu. “We were surprised by the overwhelming responses from the knitting community, not just in Japan but in other countries as well,” Meri says.

After a couple of years, the ladies printed their magazine and sold copies to yarn and book shops around the world. As their patterns, DIY ideas, and fanbase expanded, they embraced the challenge of opening a flagship knitting goods store—Walnut—near Karasuma Station.

Thinking outside the (bento) box

For Thomas Bertrand, a French expat living in Japan for university, it was a conversation with his mom—about bento boxes being featured in one of her magazines back home—that sparked a lightbulb moment. “I was a hundred percent sure that bento boxes could sell well because, in every country, people prepare food and pack lunch.” Thomas had been blogging about his expat musings, including how people from Kyoto primarily bought bento boxes in supermarkets or department stores. No one seemed to think “about having a shop that’s only bento boxes.”

Thomas experimented online, first by selling bento boxes to French and English markets. Then he launched a site in Japanese, attracting the attention of locals in Kyoto. After moving to a new apartment near Nishiki Market, he noticed how many tourists passed by and enjoyed the street food. Motivated by the foot traffic, Thomas signed onto the first storefront he saw and found a physical location for Bento&Co. He’s betting that visitors who taste the nearby dango, tako tamago, or yukke will want to take a piece of Japanese food and culture home.

Three expats walk into a bar...

A Welshman, a Canadian, and an American walk into a bar in Aomori, Japan, then leave and open their own brewery. No, seriously. Over a decade-long friendship, Benjamin Falck, Paul Seed, and Chris Hainge often snowboarded together and conducted “research” on Japanese beers. But they realized that in order to find their ideal micro lager, they had to get more hands-on. Chris dove into home brewing and “started submitting beers for contests and winning accolades,” recounts Paul. The trio grew more serious about their beer-domination plans—Chris trained with famous breweries, while Paul crafted a business plan as part of his MBA. Chris even convinced his buddies to leave Tokyo—and their jobs—to start the Kyoto Brewing Company.

Not everything went according to plan. “We were shocked by how difficult it is to get financing in Japan,” says Paul. So he and the team put even more on the line, rallied investments from family, friends, and old colleagues, and built the brewery from scratch within the Minami ward. Being in a residential area, the trio worried that their neighbors might not frequent their tap room—but the community came with support. These days, the tap room sees upwards of 300 visitors a day when open on the weekend. Paying homage to Kyoto and its appreciation for the seasons, the gents brew two types of beers (“Four Seasons” as well as “On a Whim”), each with their own original recipe that changes every season. They also collaborate with local food trucks by inviting them to serve on the premise. “Dashimaki” omelettes and “nakama” (friendship) brew, anyone?

Feels like home

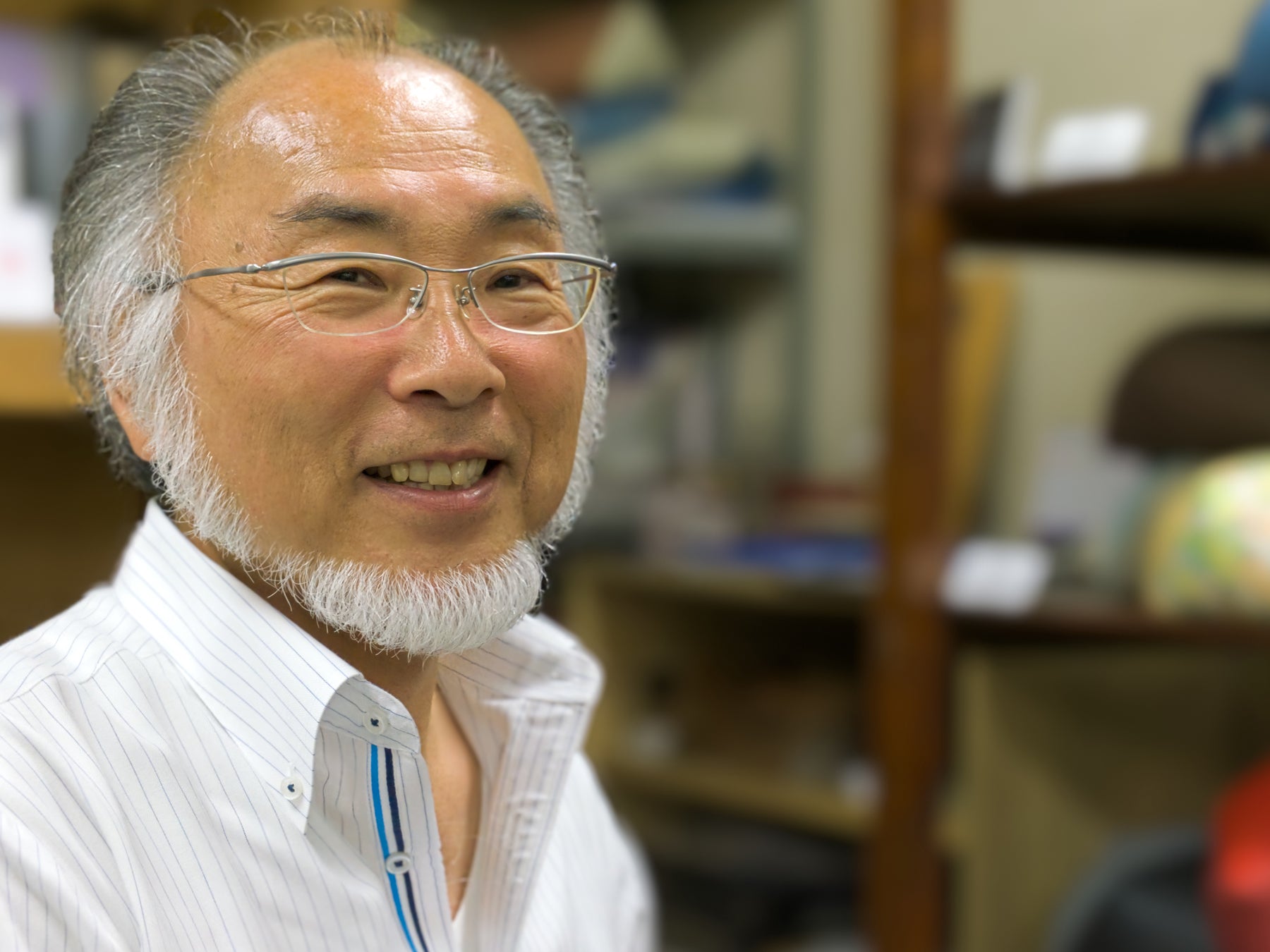

When it comes to relaxation, the term “kutsurogi” encapsulates the essence of feeling at home—or chilling out. Takaokaya, the makers of zabuton floor cushions and hand-stitched futons, are the epitome of “kutsurogi” for their customers but are adapting to a generation of buyers who’d rather Netflix and chill. Koichiro Takaoka, the third-generation owner of this century-old business, never thought he would run the family shop. As a kid, he says, “I wasn’t so interested in this then.” But while the eldest of four brothers found his parents’ obsession with futons, frankly, boring, he missed home after working in trading in Tokyo and Thailand.

Koichiro used his experiences of working abroad and leveraged the rising global interests in Japanese craftsmanship by showcasing Takaokaya’s products internationally. He’s since modernized operations. Takaokaya’s flagship store in the Shimogyō-ku ward is sleek, minimal, and angularly designed by local architects. “We’re using modern patterns and fabrics for people who want to use zabutons for their sofas,” Koichiro notes. “We make more casual styles for young people.” That includes vibrant polka dots, funky kimono-inspired patterns, and newer forms of mini-zabutons that are increasingly finding their way to homes across Asia, Europe, and the US.

Steeped in culture

Located just five minutes outside of Kyoto Station, Kurasu is no ordinary cafe. This specialty shop—with its curated beans and matcha lattes with espresso—is the essence of coffee culture in Japan. It treats brewing as a craft and is backed by a loyal following both on and offline, the roots of which started to grow over five years ago when owner Yozo Otsuki left his finance career and relocated with his wife to Sydney, Australia. Many of his new friends admired his collection of Japanese housewares, and he was inspired to start an online business to share such items beyond Japan.

As a son of two jazz “kissaten” (Japanese cafe) owners, Yozo returned to his roots as he increasingly focused his business on coffeeware to showcase the Japanese way of home brew. Yozo’s interests in beans intensified, so he started a monthly subscription, offering a selection from artisan Japanese roasters to the rest of the world. International fans were keen to visit when they came to Japan, so Yozo launched a cafe in 2016. It feels like a modern echo of old Kyoto, with its sleek gray-tiled exterior and minimal white interior that’s partially covered with wooden panels. Coffeeware and brewing equipment is on display, and staff members speak English to help bridge visitors to traditional Japanese coffee culture. What you won’t expect to find but will: bow ties—created from repurposed kimono fabric by Kyoto artisans in a spinoff venture Yozo dubbed Kimonono.

Feature image by Ryan Kalinka

Additional reporting and photographs of Takaokaya and Koichiro Takaoka by Zara Stone

Read and watch more from our series, And Nowhere Else, by exploring the tight-knit retail community of Key West, Florida. The city opens its arms to outsiders, and the result is a mixed bag of adventure-seekers, displaced artists, retirees, and “oddballs.”